The following blog post is part of a series highlighting key aspects of the work of DNA Doe Project’s investigative genetic genealogists showcased in the documentary Naming the Dead, available on NatGeoTV, Hulu, and Disney+.

Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG) is an incredible tool for solving cold cases and identifying unknown remains, but when cases extend beyond a researcher’s borders, the researcher’s job gets much harder. The global nature of human migration and the shared ancestry of populations mean that international connections are increasingly common, but they bring a host of unique challenges.

Varying Legal and Privacy Frameworks

This is arguably the most significant hurdle. Data privacy laws differ wildly from country to country, and what’s permissible in one jurisdiction might be illegal or highly restricted in another.

- GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). Europe’s GDPR is a prime example. It is one of the strictest data protection laws globally, classifying genetic data as “special category personal data” requiring a higher level of protection.This can significantly limit how genetic data obtained from crime scenes or unidentified remains can be uploaded, stored, and processed, especially if it involves individuals residing in EU countries or if the data itself is processed within the EU.

- Consent Issues. The concept of “informed consent” for DNA databases varies. In some countries, individuals might explicitly opt-in for law enforcement matching, while in others, such a feature may not exist, or data sharing for law enforcement purposes could be prohibited entirely. The idea of “relational privacy” – where one person’s genetic data inherently reveals information about their relatives – creates complex ethical dilemmas across borders.

- Jurisdictional Conflicts. Determining which country’s laws apply when DNA data crosses borders can be a legal minefield. A crime committed in one country might have a suspect whose closest genetic relatives live in another, leading to a clash of legal systems.

- Lack of Precedent. Many countries are still developing their legal frameworks around IGG. This creates uncertainty and a lack of clear guidelines for law enforcement and genetic genealogists.

Limited or Inaccessible DNA Databases

While the major DNA databases (like AncestryDNA, 23andMe, MyHeritage DNA, GEDmatch, FamilyTreeDNA) have millions of users, their geographical distribution is not uniform.

- Population Representation. Many databases are heavily skewed towards users of European descent and those residing in North America. This means that if a case involves individuals with ancestry predominantly from Asia, Africa, or certain parts of South America, the chances of finding close genetic matches are significantly lower.

- Database Availability. Some countries may not have commercial direct-to-consumer (DTC) DNA testing companies or open-source platforms that are accessible for IGG purposes. Or, if they do, their user base might be too small to be effective.

- Restrictions on Law Enforcement Access. Even if a database has users from a relevant country, that country’s laws (or the database’s terms of service, influenced by those laws) might prohibit law enforcement access to their data.

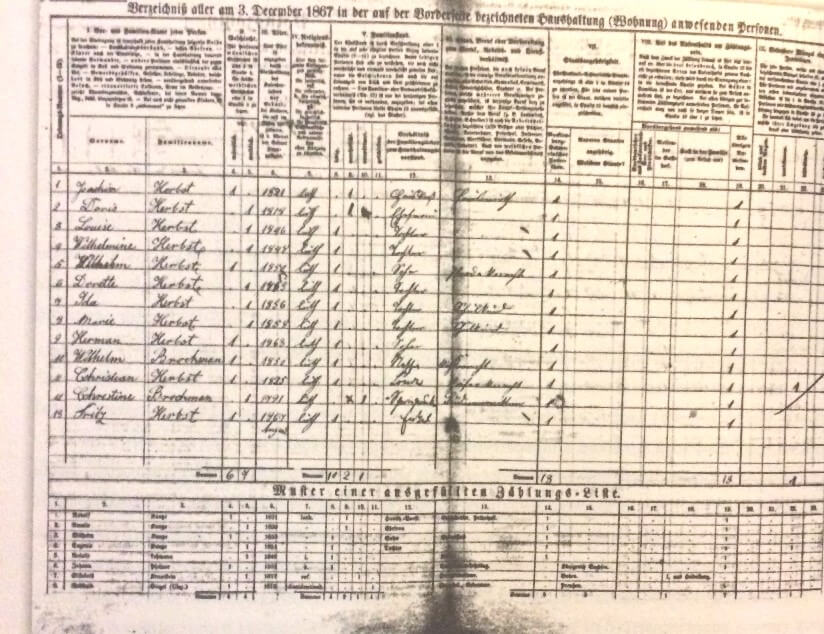

Record Accessibility and Language Barriers

Traditional genealogical research, a cornerstone of IGG, becomes exponentially more difficult when dealing with international records.

- Decentralized Records. Unlike some countries with centralized vital records, many nations have highly decentralized archives, with records scattered across local churches, regional government offices, and private collections.

- Access Restrictions. Many countries have stricter privacy laws on historical records, limiting public access to birth, marriage, and death records for longer periods than in the US.

- Language and Script. Researching records in unfamiliar languages and non-Latin scripts (e.g., Cyrillic, Arabic, Chinese characters) requires specialized linguistic skills or the costly assistance of professional translators.

- Cultural Nuances. Understanding naming conventions, social customs, and historical events crucial for interpreting records requires deep cultural knowledge.

“I had trouble finding my Hungarian great-grandmother Anna Sztankovics in passenger lists even though I knew she immigrated to the US in the early 20th century. The key was understanding local naming traditions. Hungarian women traditionally adopted their husband’s surname and added the suffix “-né” to his given name. This construction appeared in official documents and indicated the marital relationship. Anna was married to István Morvai when she immigrated; I found her Hungarian marriage record, which noted her “new” name, and I searched for that. “Morvai Istvanné” arrived at the Port of New York in 1909. “

Erika Korowin, DDP Investigative Genetic Genealogist

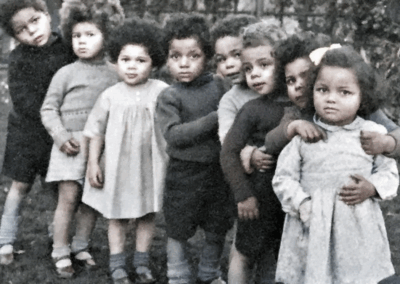

Endogamy and Pedigree Collapse

These genetic phenomena, while present in all populations, can be particularly challenging in populations that have historically married within a small community or geographic area.

- Dense Trees. Endogamy (intermarriage within a group) results in DNA matches who are related through multiple lines of descent. This makes it incredibly difficult to pinpoint the most recent common ancestor and accurately build out a family tree.

- “False” Closeness. A DNA match might appear to be a closer relative (e.g., a second cousin) than they actually are due to multiple shared ancestral paths, leading researchers astray.

Ethical Considerations and Repatriation

International IGG often touches upon sensitive ethical issues.

- Indigenous Populations. Research involving indigenous populations requires extreme sensitivity and respect for their cultural protocols, often involving community consultation and specific ethical guidelines.

- Repatriation of Remains. For unidentified human remains, international IGG might lead to identification in a country far from where the remains were found. This raises complex questions about repatriation, cultural sensitivities around burial, and the wishes of surviving family members in a different cultural context.

While the allure of IGG to solve global mysteries is strong, the reality of international casework is full of complexities. Overcoming these challenges requires not only advanced genetic genealogy skills but also a deep understanding of international law, cultural nuances, linguistic proficiency, and a commitment to ethical practice.

As IGG continues to expand globally, international collaboration and the development of standardized ethical and legal guidelines will be crucial to its effective and responsible application across borders, and the DNA Doe Project remains committed to doing all that we can to support law enforcement in their work to solve these challenging cases.

For more information about how you can help the DNA Doe Project, please click here.